This Spring I did an interview with Katherine Neebe, Chief Sustainability and Philanthropy Officer, SVP National Engagement and Strategy at Duke Energy, for a piece in the Harvard Business Review on CSOs that I wrote with Professor Alison Taylor. We had briefly met when she was at Walmart, but this was my first opportunity to have a long conversation with her. It was fascinating and I learned a great deal about what it means to be a CSO in an electric utility company. I also learned a lot about the central role utility companies play in the energy transition. I asked Katherine if she’d be willing to do an interview with me and she kindly agreed.

Katherine Neebe, Chief Sustainability Officer, Duke Energy | © THE MACHINE PHOTOGRAPHY

Eccles: To get started, please tell me a little about your childhood. Where did your passion for sustainability come from?

Neebe: I was born and raised in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. My father was a professor at UNC’s business school where he taught statistics and operations. My mom was the executive director of a childhood research institute. While they have both since retired, I was raised with a deep respect for family and academics.

While there wasn’t a singular event that drove my passion for sustainability, I think it’s affiliated with one of the things that was impossible to escape as a kid. There wasn’t much that was bigger in the 80s and 90s in my hometown than the Tar Heels and, specifically, Dean Smith. Of course, many remember Coach Smith for what he was able to achieve on the court. And part of his success was his approach to coaching, a style which emphasized leadership by example, doing the right thing, and valuing different perspectives and talents.

But, more importantly, he also used his voice and position to advocate for civil rights, and in the process, transformed Chapel Hill, the South, and basketball for the better. So it wasn’t that he was just great at his job but also that he was able to leverage the power structure he worked within to make the world more equitable. While I wouldn’t necessarily position his work as “sustainability,” the standard he set is one that I’ve always aspired to follow.

Eccles: Speaking of education, tell us about what you studied in school. What is the biggest/most important lesson you learned.

Neebe: As an undergrad, I received a BA in English Literature from Colorado College. While a liberal arts background made it a little more challenging to land my first official job, which coincidentally was for the Tar Heels, I have come to really appreciate that education. First, in sustainability, it is important to be able to communicate in a way that not only inspires and empowers, but also demonstrates clarity, understanding, and transparency. Second, critical thinking is an essential skillset in this field as it helps ensure a more expansive framework for problem solving and can ward off the risk of unintended consequence.

Eccles: Nice about Colorado College. I grew up outside Denver! How did you break into sustainability?

Electricity, environment and ecology concept – close up of hand holding energy saving lightbulb (Photo: iStock)

Neebe: My first job in sustainability was back in 2000 where I was charged with developing marketing campaigns and promotions to convince people to swap incandescent light bulbs with more energy efficient compact fluorescent bulbs. The work involved a lot of partnership with the utilities who funded the program, as well as retailers, manufacturers, and NGOs. And, at the risk of stating the obvious, the cost, quality, and convenience of the product were the messages that resonated with customers. Certainly, customers could appreciate the environmental attributes of the light bulbs, but generally only after they had already decided to make a switch.

About a year into that job, Enron happened and, as a result, customer utility bills spiked. For many, the easiest way to mitigate against those higher bills was to install a more efficient product. So, in what felt like moments, the market shifted as demand for energy-efficient light bulbs grew and kept growing. To this day, I’ve not seen a market grow so rapidly for a more sustainable product, one where consumer prices dropped practically overnight, and shelves were cleared as quickly as they were stocked. And the greenhouse gas (GHG) benefits felt both meaningful and tangible. It was a remarkable moment in time, and I was hooked.

Eccles: That’s a fascinating story and one I’d never heard so thanks for sharing. What did you do after that?

Neebe: I wanted to be smarter about how business and environmental and social issues intersect, so I decided to go back to school to get my MBA at the Darden School at the University of Virginia. At the time, sustainability was still in its nascency, and I did not have a resume that necessarily conveyed confidence to corporate America. So, I thought an MBA would help me learn both the fundamentals of business and open doors that might have otherwise been closed.

I graduated from business school in 2004, which was slightly ahead of when corporate America started to engage more meaningfully on what was then referred to as corporate social responsibility. While I had all the passion and some experience to work in the field, I didn’t have a lot of full-time opportunities. I spent the next three years trying to make things come together. In short, this meant I jumped around a lot, taking on projects that ranged from the sustainability of hog farms in eastern North Carolina to emissions affiliated with diesel engines. I learned a lot but finding both a steady paycheck and meaningful work was a challenge.

WWF threatened vunerable endangered animal campaign posters and publications in Preston, Lancashire, UK. The World Wide charity Fund, posters & publications, for Nature is an international non-governmental organization founded in 1961, working in the field of the wilderness preservation, and the reduction of humanity’s footprint on the environment (Photo: Alamy)

Eccles: I admire your persistence! I know you finally got a job at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). How did you get the job and what did you do there?

Neebe: I remember WWF posted an opening for a job that essentially asked, “Do you know business? Do you care about the environment? Apply here.” When I went into the interview, I found that they were intentionally vague because the job and the partnership that I would ultimately manage wasn’t yet public. And it was a dream job. One where all these disparate experiences I had in sustainability finally came together and made sense.

In 2007, WWF hired me to lead one of the world’s largest corporate-NGO partnerships, a $20 million sustainability-driven initiative with the Coca-Cola Company. The focus of the partnership was to conserve seven iconic river basins, improve the efficiency of the company’s water use, decrease the company’s carbon dioxide emissions, and support sustainable agriculture and packaging. In the fullness of time, the partnership grew to a $97 million platform that stretched across 45 countries and expanded to take on polar bear conservation in one of the largest cause marketing initiatives ever executed by the company.

Eccles: Best as I recall, back then the NGO and corporate worlds were more into conflict than collaboration. How was this initiative received on both sides?

Neebe: It is much more common now for NGOs to partner with companies to address environmental and social concerns. However, when we launched the partnership to the public back in 2007, it was front page news. People were skeptical that these “unlikely allies” could work together to mitigate environmental risks and create business value. We had a lot to prove. And we did. We were able to find common ground, identify meaningful steps we could take that advanced WWF’s mission while also supporting Coca-Cola’s business, and hold each other accountable. Transparency was also something we were very intentional about—with each other and with the public. We were clear about the sustainability goals we set, how we measured our performance, and where we were making (and falling short of) progress.

Eccles: You then went to Walmart. Why did you make this move?

Neebe: In 2013, I was ready for a new challenge and accepted an offer to join Walmart’s sustainability team. Initially I led stakeholder engagement; over time, my role expanded to include international policy and issue-based projects such as sustainable seafood, deforestation, and human rights. In my final few years with the company, I established and led the ESG (environmental, social and governance) function on behalf of the enterprise. It seems wild from the standpoint of today, but very few even knew what the acronym ESG meant five years ago, let alone how hotly debated a topic it would become. I appreciate that there is a lot of conversation right now about what the role of the corporation should be when it comes to environmental and social issues and how any actions taken need to demonstrate risk mitigation or value creation—for the business and for the stakeholders served.

Logo of Duke Energy | © DUKE ENERGY

Eccles: You have a diverse background working in sustainability. You made the move to Duke Energy three years ago. Tell me a little bit more about what you do there.

Neebe: The clean energy transition is something that sustainability professionals have been talking about for decades. But it’s here now, and I’m fortunate to have a front row seat to help make it happen. I lead our enterprise-level stakeholder engagement efforts to develop solutions to meet customer needs for continued reliable and affordable energy while simultaneously working to achieve our goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. In addition, I maintain oversight of the Duke Energy Foundation, which provides $30 million in philanthropic support to help meet the needs of communities where Duke Energy customers live and work.

One of the reasons I came to Duke Energy is because we are leading one of the largest clean energy transitions in the country. Our mission is to power the lives of our customers and the vitality of our local communities. As energy demand doubles and possibly triples by 2050 across our service territory, we need to significantly grow energy generation, retire 16 gigawatts (GW) of coal, and modernize the energy grid. We need to do that in a way that provides reliable, affordable, and accessible energy while also meeting our net-zero ambition. The engineering, environmental, and social considerations to achieve this are significant. But there’s a real upside to the story too. As we look at our 10-year $145 billion capital spending plan, we anticipate that our clean energy transition is expected to bring roughly $250 billion in positive economic outputs, from job creation to property taxes.

But those benefits aren’t all future focused. For example, our economic development team continues to be successful in attracting growing companies to the communities we serve. In 2022 alone, the team secured 89 projects resulting in more than 29,000 new jobs and over $23 billion in capital investments. In addition, our supply chain spend is also an important avenue for strengthening local economies. Last year we spent $14 billion overall on supplier goods and services, more than $5 billion with local suppliers and over $1.8 billion with diverse suppliers.

Duke Energy Solar Power Facility in Mocksville, North Carolina | © DUKE ENERGY

Eccles: Let’s dig in a little on the energy industry. Duke Energy has ambitious climate goals. How are you driving change in your role?

Neebe: We have net-zero from electric generation goals by 2050 for Scope 1, 2, and certain Scope 3 carbon emissions and net-zero methane goal by 2030 for our natural gas business unit. That means that 95% of our calculated GHG footprint, from our own emissions to those across our value chain, is now encompassed in a net-zero goal. In 2022, we took additional steps toward action on climate change by targeting energy generated by coal to represent less than 5% of total generation by 2030 and to fully exit coal by 2035 as part of the largest planned coal fleet retirement in the industry. To date, Duke Energy has already seen a 44% reduction in Scope 1 carbon emissions from electricity generation since 2005.

With our net-zero goals established, we also need to consider the social issues affiliated with the clean energy transition from the impact of coal plant retirements (also known as the just transition) to where we site and build new infrastructure (including topics such as environmental justice and NIMBYism) to guardrails for those low-income customers who may be struggling with meeting basic needs. Again, I’d reinforce that there is a net positive economic upside to our clean energy transition; our role is to manage the risks and the value creation in a way that is balanced for our customers and communities.

Eccles: Thinking through the balanced approach to the energy transition. What is your view on the energy mix of the future in terms of existing and new technologies?

Neebe: We have a clear line of sight into how we can achieve approximately 70% of our carbon goal by using technologies that are available today. Among our plans, we anticipate retiring 16 GW of coal as well as building 30,000 megawatts (MW) of renewables (that’s about five times the amount we have today) and 10,000 MW of energy storage all by 2035.

I’d highlight the role two technologies play as we think about decarbonization beyond what I’ve outlined above, both of which are subject to a lot of discussion. First, in the near term, natural gas helps ensure reliability and enables us to accelerate the retirement of our coal fleet while adding more renewables. It also provides flexibility and adaptability to quickly dispatch reliable, affordable energy under challenging circumstances, such as extreme weather events. Over time, we expect to be able to transition our remaining natural gas generation to burn increasingly clean fuels, like green hydrogen and renewable natural gas.

Duke Energy Transmission Lines | © DUKE ENERGY

Second, nuclear is an important source of carbon-free capacity that exists today. We operate the largest regulated nuclear fleet in the nation, and carbon-free nuclear energy already provides approximately 50% of our energy in the Carolinas. Last year our nuclear fleet generated more than 73 billion hours of electricity and avoided the release of 49 million tons of carbon dioxide.

Beyond the generation side of the equation, over the next 10 years, we anticipate a $75 billion investment in our grid—the nation’s largest investor-owned grid—to modernize and strengthen it to connect renewables, improve reliability and resiliency, and help protect it from cybersecurity and physical threats. Both our generation and the grid must work seamlessly together as we deliver increasingly clean energy to our customers.

As we consider technologies beyond those that are commercially viable and exist at scale today, we estimate that we need over 40,000 MW of new dispatchable zero-emitting load-following resources (ZELFRs) to achieve our net-zero goal. ZELFRs can include new nuclear, including small modular reactors, advanced energy storage, and turbines that run on hydrogen or biogas.

Eccles: I find the energy transition a fascinating topic. As you decarbonize, it seems that would impact other industries. Right?

Neebe: I think one of the unappreciated stories when it comes to action on climate is the role that U.S. electric utilities have played in reducing GHG emissions. As a sector, since 2005, we have led the way and reduced carbon emissions by nearly 40%, while emissions from most other economic sectors have remained generally flat or have increased with economic growth. Transportation is now the highest emitting sector in the U.S. And all major U.S. utilities now have net-zero goals. As we respond to increased electrification, economic growth, and other needs on the energy system, not only do we anticipate a higher demand for our increasingly clean “product,” but we are also going to play a key role in reducing the emissions of adjacent sectors; transportation is a good case in point.

Eccles: It seems that it takes a lot of people working together to make progress. As CSO, I imagine the role has progressed beyond reporting – although that is still a part of the role—but it seems to be more focused externally and how you engage with stakeholders. As a corporation today there seems to be a lot of pressure from stakeholders. Talk us through how you navigate this.

Neebe: Sustainability is strategy. It’s about identifying the relevant environmental and social issues to a business from a risk mitigation or value creation standpoint, understanding not only what needs to change in the system but also what specific actions a company should take, implementing an action plan, embedding the work in the business, and finally being as transparent as possible about your progress and your challenges. Trust starts with transparency. And we can’t solve for any of this in a vacuum. Stakeholder engagement is foundational to our business success. We need to work with people who have different expertise, perspectives, and experiences to find common ground where we can collaborate and move toward our shared goal of a cleaner and brighter energy future for all.

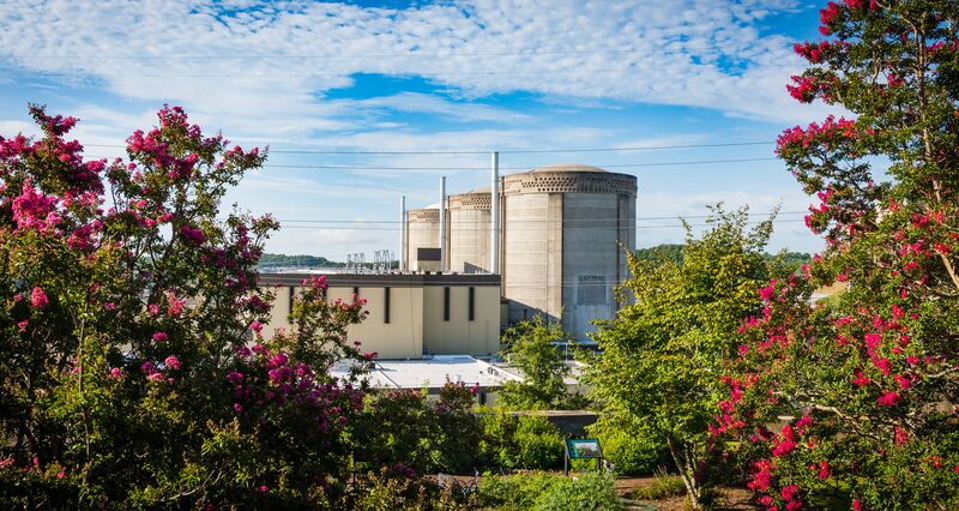

Duke Energy’s Oconee Nuclear Station in Oconee, South Carolina | © DUKE ENERGY

Eccles: Thanks again for your time. I’ve learned a lot. And thanks for the important work you and Duke Energy are doing to support the energy transition in America. I know utility companies have a lot of critics and I hope at least some of them will read and learn from this interview.

Neebe: Thanks, Bob. Let me end by saying we believe deeply in engagement and are always happy to talk to and learn from others.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Subscribe our newsletter to receive the latest news, articles and exclusive podcasts every week