Claude Letourneau, CEO Of Svante, Discusses The Essential Role Of Carbon Capture Storage And Utilization

I met Claude Letourneau a few weeks ago at a private gathering of climate and energy CEOs and leaders organized by one of the world’s largest financial institutions. While I’m no expert on carbon capture and storage (although I have written about it with someone who is), I was very intrigued to learn about what he’s doing in building the world first fully integrated carbon management company.

Today, all eyes are on one odorless, invisible waste product whose effects are nonetheless undeniable: CO2. Human activities pump out more than 36 billion metric tons of CO2 every year, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Mother Nature absorbs about half of this through plants, trees, and the oceans. That still leaves about 18 billion metric tons of CO2 per year accumulating in the atmosphere. That’s a staggering amount.

I sat down with Claude Letourneau, President & CEO of Svante, to discuss his perspective on the carbon management market, the challenges and opportunities that the growing carbon management landscape presents, and the important role that he sees capital playing in the deployment of this climate solution for the ‘’Green Industrial Transition.’’

Claude Letourneau, President & CEO, Svante

Eccles: Claude, thanks for taking the time. For starters, tell me a bit about your background.

Letourneau: I grew up in Quebec City after living in Germany when I was 10 to 14 years old. My dad was posted on a Canadian military base to open a school for the French-Canadian students. Very young I developed an interest in chemistry and how to make things. After graduating from Laval University in Chemical Engineering, I met a professor who exposed me to Technology Management and Strategic Planning. He was my mentor for several years and taught me to become a CEO of a technology-based company. I was hooked on managing the innovation process.

Eccles: Your mentor was clearly a very formative person in your life.

Letourneau: Yes, he was. For more than 30 years, I’ve been helping both start-up and incumbent companies manage the transition created by disruptive technology innovation and/or shift of business model. I develop business transformation plans and go about implementing it with courage. Change requires effort and courage—the courage to challenge the status quo, the courage to get out of one’s comfort zone, and the drive to move forward on how to convince people, not just to accept change, but be invigorated rather than threatened by change.

My career has consisted of real-life experiences in changing various diversified industries (engineering/construction, advanced thin film lithium polymer battery development, magnesium smelting, power electronics, telecom, polymeric membrane development, and design-build of large capital projects). It has given me the taste of the rewards of change with a common mission to find solutions and business opportunities to mitigate carbon emissions.

I’m a self-starter with an orientation to action and to get results steering large-scale projects from laboratory inception to full-scale industrial implementation. My technical and communication skills and intuitive capacity to make connections between strategy and capability allow me to create a supportive and urgent environment for new product and service development.

Eccles: I see the evolution of your career and it makes sense. You have the qualifications needed to pull of something much bigger than you’ve ever done. But we’ll get to that in a minute. Where does the name of your company come from?

Svante Arrhenius (1859 – 1927) Nobel prizewinning electrochemist at work. | (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Letourneau: We named the company after the Swedish scientist, Svante Arrhenius, who in 1896 was one of the first people to establish the link between CO2 going into the atmosphere and the increasing temperature of the planet. In this way, we are like the Tesla of carbon capture. We have the ambition to become the world’s first fully integrated carbon management company. We were originally active in the purification of hydrogen for the fuel cell market. As that market did not get off the ground, we switched to CO2 capture. I came on board in 2017 when we had 25 employees and money in the bank for two months. Since then, we’ve raised $500 million of private equity and now have 300 employees.

Eccles: Great story! I want to hear more about Svante but I think some context first would be useful. I know you have some distinctive views on that.

Letourneau: The vision of a green future means a world humming with the invisible flow of sustainably-generated electrons that power our devices, data centers, and light up our cities. But beneath this glow of energy lies a reality hidden in plain sight: the molecules of steel, concrete, glass, and plastic that make everything from phones to buildings arrive via industrial processes that send vast amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. As the source of nearly one-quarter of global CO2 emissions, the industrial sector is increasingly pressed to identify and deploy solutions to cut those emissions.

Climate investing is the largest collective human undertaking within the next 30-year period that we will ever see. Aside from the massive deployment needed of renewables and electrification of our energy system, we need to pay attention to the rewiring of the industrial sector by reducing CO2 emissions, not reducing our energy choices, to make products for our day-to-day lifestyle. I call this the ‘’Green Industrial Transition.’’ We need to recognize that we all had been playing with an externality that we just didn’t know was there because we cannot see and smell CO2. The impact of extreme weather conditions is now becoming a shocking reality to some of us.

Eccles: Can you please explain what you mean by “rewiring of the industrial sector” and how that relates to investments in renewables?

Letourneau: Happy to, but first let me say there is no silver bullet. Carbon management is one of many climate solutions. If deployed rapidly at scale it will provide more “bang for our buck’’ than people realize. We think that the capital investment needed in the energy transition—for renewables, electrification of vehicles, and the like—is about $120 trillion compared to only $2 trillion that will be required for capturing CO2, around 10 gigatons (or 10 billion tons) per year. When you do the math, the world needs to deploy 10,000 carbon capture plants over the next 30 years.

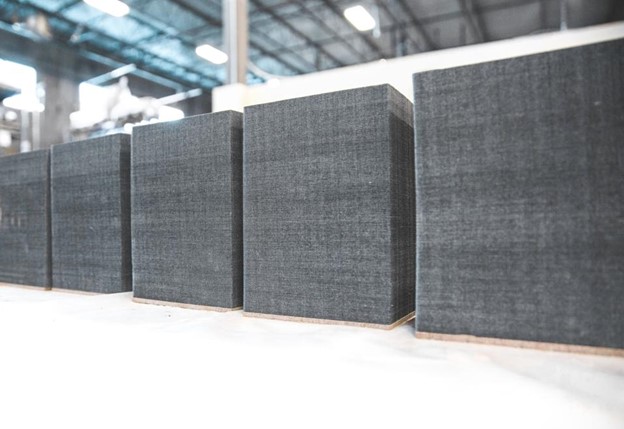

Sheets of material coated in Svante’s solid sorbents get stacked to make the company’s structured adsorbent beds, known as “filters”

Eccles: That’s a lot of carbon! But where do these numbers come from? And is this carbon capture from point sources or does it include direct air capture as well?

Letourneau: I realize some of this scale is a daunting prospect but achievable when compared to the market size of other large industries. If you think about that, putting carbon back underground, where it came from, is the size of the market for the oil & gas industry today.

Eccles: Sounds like a big opportunity, but when I wrote that piece (mentioned above) with Philip Rossetti of The R Street Institute on carbon capture storage and utilization (CCUS) we mostly got negative feedback, some of it quite vituperative. One major pushback was the cost. What’s the deal here?

Letourneau: The feedstocks of this Green Industrial Transition will be capital and the physical CO2 molecule. The paradigm shift we need to do as a society, to understand the carbon intensity of products we enjoy in our day-to-day lives, will be the key driver to enable the public acceptance of paying to mitigate the carbon footprint of products at a cost similar to managing our rubbish (i.e., $1,500 per capita or $150/ton CO2). CCUS has emerged as an important means to manage the emissions of carbon dioxide.

Eccles: Thanks. That’s helpful and I like the analogy. But do you think people will really be willing to pay that amount?

Letourneau: In short, yes, but this will require government action. Cracking the code of CO2 monetization will also require public education about the social cost of carbon and its effects on our day-to-day life. The social cost of CO2 is the economic damage caused by each additional ton of CO2 in the atmosphere. This accounts for things such as crop damage, losses from natural disasters, health impacts, and more caused by extreme weather.

The U.S. government has determined the social cost of CO2 emissions to be $190 per ton, and experts say that could reach $300 per ton in the next decade. This projected increase underscores the mounting price tag attached to climate inaction. As long as the cost of carbon mitigation is lower than the social cost, it makes sense to invest in carbon management. And once the government has set rules and pricing for carbon, industrial buyers will no longer bear the risk of the cost to implement CCUS.

Governments are uniquely able to address the gap between the true social cost of carbon and what companies have to pay today to freely emit. Emitting carbon is like using a credit card—sooner or later, the bill must be paid. Failure to act now means it will only be more expensive to act in the future.

A row of Svante’s nanoengineered filters sits on a table for industrial carbon capture at facilities including cement, pulp & paper, steel, and more.

Eccles: Makes sense. It seems inevitable we put a price on carbon and the sooner the better. But this will be very difficult to do in the current political environment.

Letourneau: Yes, there is a great deal of polarization between conservatives and liberals when it comes to climate solutions, but we need to get past that. We need a bipartisan climate approach working right-of-center focusing on action.

Eccles: You know I couldn’t agree more and this has been a major focus of mine. But moving on When we met, I remember you talking about “the carbon management industry.” Please explain what that means.

Letourneau: The analogy I could draw is the waste management industry for the ‘’What’’ and the commercial aircraft industry for the ‘’How’’.

On the WHAT, we need an engineered solution for carbon management as we have for waste management—a way to collect, transport, and store or reuse the world’s excess carbon.

On the HOW, we believe there will be just a few players who could deliver such solutions at a mass scale. With our carbon capture filter technology, we would be to the carbon capture storage and utilization (CCUS) industry what Rolls-Royce or GE are to Airbus and Boeing—the engine developers for the aircraft manufacturers or the “filter inside’’ every carbon capture and removal plants. In our space, however, there are no equivalents to Airbus and Boeing yet. Those will probably be major engineering and construction companies building commercial carbon capture plants.

Eccles: How does Svante fit into this?

Svante’s carbon capture pilot plant at Chevron’s Kern River asset in San Joaquin Valley, California. The plant has the capacity to capture 25 tonnes of CO2 per day and has been in operation since 2023. The project is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Cooperative Agreement No. DE-FE0031944.

Letourneau: At Svante, we are a builder and scaler by manufacturing solid carbon filters, building carbon capture and removal plants, and leveraging our human resources in project development. We are delivering at scale with a “build it, and they will come” model. In line with this mindset, Svante is building a $145 million filter manufacturing facility to support 10 million tons per year of CO2 capture. This is factory No. 1 on its way to 100 million tons per year of cumulative capacity to support the gigatons carbon management industry.

But competitive carbon capture economics and plant performance are necessary but not sufficient. We have developed a unique Customer Value Proposition which is allowing us to win projects in segments and geographies where they create the most value for customers. We have a clear understanding of the key drivers and friction points to secure industrial customers.

Eccles: Given the scale of the opportunity and the complexity of delivering on it, you must need to have partnerships of many kinds. How do you find the right ones?

Letourneau: Yes, collaboration in our space is paramount as there are so many different types of specialized expertise required in the field to get projects done. Since we specialize in providing the technology and equipment for carbon capture and removal—the “engines” of a carbon capture plant—we needed to find partners equivalent to Boeing and Airbus in the engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) space. That’s why we partnered with Kiewit, Samsung Engineering, Technip Energies, and others.

In addition to our EPC partners, we also collaborate with two other types of companies. Firstly, we attempt to find partners who have the capacity to scale up manufacturing of our own technology, such as the nanotechnology sorbent materials that selectively grab onto carbon molecules and releases other gasses such as nitrogen. Examples are BASF and 3M as they are specialists in the coating technique required to mass produce our filters. Secondly, we look for partners and suppliers aligned on speed, massive scale, and low costs to deliver the necessary auxiliary equipment to provide an integrated solution.

Eccles: Sounds like Svante is in good shape, but what must be done now?

Svante’s 141,000 sq. ft. commercial filter manufacturing facility, The Centre of Excellence for Carbon Capture & Removal, in Vancouver, Canada. The facility supports the manufacturing of both direct air capture and point source carbon capture.

Letourneau: We must work at what I call “ludicrous speed” and we need “substantial capital’’ to build scale plants with steel in the ground and with physical goods delivered on a physical infrastructure. In terms of speed, we should think of the urgency for action as if a tsunami were approaching. Everyone seems to be waiting for the unflawed, tried and tested carbon management solution to come along, but we don’t have time for that. The climate emergency is real, and without commercial CCUS projects being rapidly deployed at scale starting now, we will miss our Paris Agreement targets. Without the ability to stop CO2 from entering the atmosphere, or removing the excess that is already there, the cost of a net-zero emissions pathway could become untenable, placing a potentially impossible burden on the speed of capacity scale-up of wind, solar, and hydrogen electrolysers.

In addition to speed, barriers need to be broken—legal, regulatory, and infrastructural. This can only happen if governments, industries, and financial institutions all work together. And on top of that, CCUS projects must have a license to operate on a social level. The world needs to get educated and onboard with the impactful difference that the CCUS industry can deliver. We are truly a complement to the other key pillars of decarbonization, rather than what critics may deem as an enabler of doing “business as usual.”

Eccles: And capital?

Letourneau: Svante’s successful standalone strategy is proceeding at pace; however, the window of opportunity to create a dominant platform has opened and scaled capital is needed to act now. Svante is uniquely positioned to act as a platform to create the world’s first fully integrated carbon management company in the market. We have enough capital for the next two years, but we’ll then need more. It will be a fraction of the total capital that needs to be raised and invested. Both the government and the private sector have essential roles to play and must work in unison.

Eccles: Thanks for your time. I’ve learned a lot. You are doing important work the world needs. I wish you the best of luck and let me know if I can help in whatever modest way I can.

Letourneau: I’ve enjoyed the conversation as well. Thanks for helping to get the word out and always happy for introductions to sources of capital!

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Subscribe our newsletter to receive the latest news, articles and exclusive podcasts every week