A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to talk with Brian Marrs, Senior Director of Energy & Carbon Removal at Microsoft about the company’s efforts to help build the market for high-quality carbon removal projects as an investor, a customer, and a first mover.

There is much to unpack in this arena, so for the first part of our conversation we went over some of the basics: what is carbon removal; what are the foundations of a high-quality carbon removal market; and what is the business case.

In the second half of our discussion, we look a bit closer at the state of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) as it stands today. We focus on some of the complications and challenges in areas like carbon accounting and how corporate purchasers of carbon removal can act responsibly in this market, as well as drive improvements for the future.

Brian Marrs, Senior Director Of Energy & Carbon Removal

Eccles: Brian, thanks again for helping the readers and me understand some of the basics of CDR and how Microsoft is involved. To quickly recap, we touched on several key topics in the first half of our discussion, like Microsoft’s carbon removal purchasing “North Stars” and the company’s longer-term efforts to help build the market for high-quality carbon removal. From what I have gleaned thus far, Microsoft is doing its best to be a responsible actor. I’d like to dig deeper into that but first I’d like to lay some conceptual groundwork.

Anyone working on climate hears the term “net-zero” all the time. However, I think it would be good to be clear on exactly what this term means. Would you mind explaining what it means for a company to be net-zero?

Marrs: These terms often can have different meanings in various contexts, and thus mean different things to broader stakeholder groups. The World Economic Forum, for example, defines “net zero” as a situation where global greenhouse gas emissions from human activity are in balance with emissions reductions/sinks. At net zero, carbon dioxide emissions are still generated, but an equal amount of carbon dioxide is avoided or removed from the atmosphere as is released into it, resulting in zero increase in net emissions. As you know from our discussion, Microsoft’s goal focuses on carbon negative, i.e. making deep reductions first and foremost, and leveraging carbon removal for hard-to-abate residual emissions and legacy, historic emissions.

Eccles: Thanks. Very clear. Let’s now dig a bit deeper into this idea of motivation. What motivates a buyer to act responsibly in the CDR market? What are the incentives for buying high quality, durable carbon removal?

Marrs: The most obvious incentive is to be able to live and do business on a habitable planet. As our CEO, Satya Nadella, has said: “for Microsoft to do well, the communities in which we operate must do well.” For all of us to do well we need to ensure a net-zero world.

It is useful to think of net zero as an equation: reductions + removal must equal zero. With this in mind, only high quality — additional, permanent, and measured & verified — CDR will drive impact towards making the math on 1.5°C climate targets work.

As we talked about in Part 1, there is a lot of variation in the quality of what is available in voluntary carbon markets today and not enough oversight or understanding amongst stakeholders to distinguish which carbon purchases make an additional and positive difference for the climate and which ones do not. We are focused on making carbon purchases that actually have a positive impact on the planet. With a focus on impact, we place a lot of emphasis on commercial and technical due diligence in our purchasing process.

(from left to right) Microsoft’s Vice Chair and President Brad Smith, Executive Vice President and CFO Amy Hood, and Chairman and CEO Satya Nadella announcing the company’s 2030 sustainability goals.

Eccles: Well, that’s good to hear but you can’t do this all by yourself. What’s the general state of play in carbon markets today?

Marrs: Fortunately, we are starting to see increased scrutiny from investors, NGOs, customers, employees, and even regulators now working to hold companies, developers, and brokers more accountable for the carbon products in the market.

As you well know Bob, from your own involvement with ESG reporting frameworks, the trend in sustainability reporting for companies is that what was once voluntary is now becoming mandatory. Microsoft wants to be ahead of the curve in holding ourselves to high standards, especially as accounting, policy, and reporting requirements become more robust.

Eccles: You know that with my background as the founding Chair of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), the word “accounting” is going to perk my ears up. Can you tell me more about the criticisms and confusion around carbon removal accounting?

Marrs: At present, there is not a single agreed or mandatory standard for carbon removal accounting, and we think this presents a significant challenge. At Microsoft, we have advocated for a stronger system of accountability, most notably in our comments to the EU on the proposed carbon removal certification mechanism, to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) on quality guidelines, and in our publication of our own high-quality removal criteria.

In the absence of having mandated standards, we have developed our own, science-led criteria for purchasing carbon removal, and other companies and carbon removal buyers have done the same. While having these criteria helps us in our own purchasing decisions, it increases the risk that we are working in isolation from others. This also presents a challenge to suppliers and poses roadblocks to both consistent reporting and large-scale market development.

Eccles: So, to summarize, you are telling me that Microsoft would welcome more robust carbon removal accounting standards and requirements from governments, and you have some ideas on how to shape these based on your own internal experiences and lessons learned, right?

Marrs: Yes, markets are built on standards, and we cannot expect quality without the guidance of standards. Put another way, without widely accepted, practiced, and enforced standards the carbon market risks a race to the bottom, and/or we see multiple carbon markets splintering with varying levels of quality in terms of sustainability impact.

The increased attention on carbon markets generated by new regulatory reporting requirements could provoke more buying in the market where buyers inadvertently purchase tons of carbon that have the same problems that we are trying to push past within our own carbon removal program. So we should be mindful that increased transparency—which is generally welcomed in the sustainability space—must also come with increased scrutiny on claims and better tools and products in carbon markets to help companies succeed.

Eccles: This is a really critical point and something I am well aware of having been involved in sustainability reporting for a long time. I have become a bit cautious about people expecting that once reporting requirements are in place then the problems will go away. But while we are still on this topic, let me switch to another challenge I have heard about, which is how companies reconcile their own CDR accounting claims with those of national governments. Can you explain to me how Microsoft views this?

Marrs: Modeling from dozens of reputable institutions, e.g. the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the International Energy Agency, and the US Department of Energy, all show that meeting the reduction + removal math towards 1.5° C will require massive public and private investment through and beyond 2050. Robust, global, carbon accounting practices are absolutely critical to ensuring that public and private investments are recorded in a consistent, clear manner, such that resulting sustainability claims are reflective of the north stars discussed in our first chat, i.e. additionality, permanence, measurability, and environmental justice.

Practically speaking, there is a system for recording national greenhouse gas accountings via the existing Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) process. There is still much work to be done to enable private claims from corporations to intersect and co-exist in NDC accounts. Looking forward, we need a system that can integrate national and private ledgers in a manner that ensures clear, consistent claims.

Eccles: Makes sense at a general level but sounds like there is still work to be done. Could you give me an example of an integrated national and private ledger to make this more concrete for me?

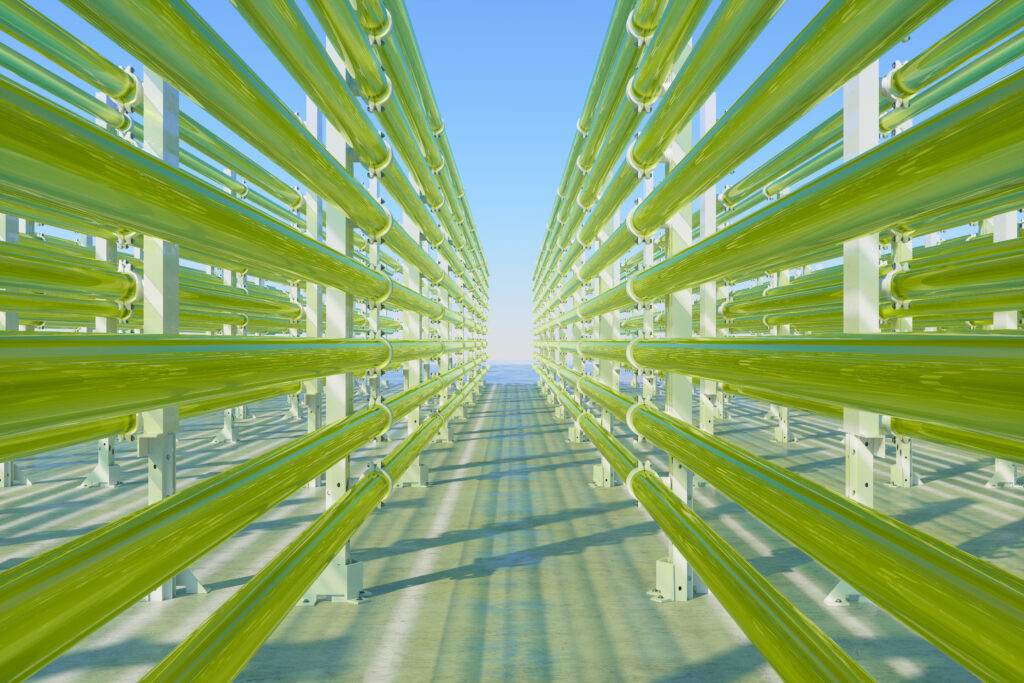

Tubular Algae Bioreactors Fixing CO2 To Produce Biofuel As An Alternative Fuel With Blue Sky Background (Photo: iStock)

Marrs: Happy to. Last year, Microsoft signed a carbon removal offtake agreement with the Danish company, Ørsted. Per the offtake agreement, Microsoft will receive 243,000 tons of carbon removal in 2030 from the Ørsted Kalundborg Hub BECCS project. Due to the carbon removal offtake agreement, we can claim full ownership rights of the carbon removals instead of Ørsted, and we will record these tons of removal against our global corporate reporting. Given that the removals will happen on Danish soil, they will be counted in the Danish geographic greenhouse gas inventory and towards the Danish climate targets. To be clear, the Danish government does not hold any ownership rights or claims to the carbon removal, but it does fall into the national accounting, much as emissions might.

A structure along those lines—with separate and transparent national and corporate accounting—should help mobilize private investments in climate action all over the world. But there is much work to be done here. More than anything, we stress the need for a global, integrated approach to carbon accounting, which would recognize the need for companies and countries to access net inflows and outflows of carbon removal. Looking at a single company or single country emissions and removals profile is insufficient.

Eccles: Well, there are some real challenges, but perhaps that is inevitable, especially in this relatively early phase and for early players, such as yourselves, trying to figure things out. How do you move forward?

Businessman holding and showing the best quality assurance with golden five stars for guarantee product and ISO service concept (Photo: iStock)

Marrs: I would reiterate that the world cannot afford to wait as we figure out each and every criticism or have implemented the perfectly integrated accounting system. Climate solutions will not scale without corporate investment, and in the system we are in now, so-called voluntary corporate action is necessary to help develop climate solutions. Investors and corporate purchases need the assurances provided by accounting and related standards. We should not forget that voluntary corporate action led to the wild success story of rapid development of the renewable energy market and subsequent drops in prices. This is not to say that successes in renewable energy offer the perfect parallel for tough challenges like scaling green materials, e.g. green steel, concrete, etc., or carbon removal. But we have a starting point for considering how public and private support can create a virtuous cycle of innovation, in part under the guidance of sensible, widely adopted standards.

We need to keep moving forward in building the carbon market and bringing more quality removal supply online, while, in parallel, having public and private sector actors work in tandem to ensure that we are reducing the risk of any inappropriate double-counting and clarifying the connection between corporate and national claims and outcomes.

Eccles: Thanks again. Coming back to what Microsoft is doing, what keeps you up at night when thinking about more buyers entering the market?

Marrs: The voluntary carbon market is both an economic paradox and an economic miracle. How can we have a market that is this large, this important, but also voluntary? A problem is that a lot of corporate buyers just look at the price per ton and focus on quantity. Right now, it is very difficult for buyers to get the sort of information we are talking about—on additionality, permanence, environmental justice, etc.—and the market does not offer this information in a consistent and often transparent way. Quality is everything in the carbon removal market. Because it is so hard for many corporate buyers to do thorough, rigorous, and quality due diligence on CDR purchases they are forced to rely on brokers and other third parties, some of which focus on sales over quality products.

Eccles: You’ve talked about quality a lot in our discussion and it’s clearly important. But I’d like to understand better the quality/quantity tradeoff.

Marrs: Many corporate buyers are focused foremost on purchasing 100% emissions coverage quantities before they focus on quality. This is perhaps predictable in a market where a low-quality ton of carbon removal that costs $5/ton can often “count” the same as a high-quality one at $25+/ton in sustainability reporting. Buyers have less incentive to prioritize high-quality purchases, which is why purchasing criteria and related standards are so important for “raising the floor” on the market. This might mean that there are less tons available today for high-quality carbon removal on the in-year spot market (meaning what can be bought and sold for immediate delivery) but the result would be a powerful signal for forward procurement to enable more robust, high-quality carbon removal supplies into the future. Purchasing less quantity of carbon removal, but higher quality carbon removal, will fundamentally reshape the market, but corporate buyers need tools to better judge quality in purchasing decisions.

Eccles: And in a similar vein, circling back to the different levels of durability, does low mean low quality?

Marrs: Just because something is lower in durability (e.g., reforestation) it does not mean it is an inherently bad solution. Nature-based solutions are proven and are currently less expensive than technologies like direct air capture, which is often higher durability, but supply is still significantly constrained. We are excited to see new technologies, e.g. remote sensing, AI-driven analytics, etc., bring new options to putting greater certainty around measuring and verifying carbon removal behind nature-based solutions. It is also worth noting that nature-based solutions can bring significant benefits to biodiversity and local communities, so there are notable co-benefits beyond carbon removal.

The takeaway here is to pursue a variety of different carbon removal solutions, that are all focused on additionality – meaning that the project directly and measurably results in emissions reductions or removals. As we discussed in our first chat, a pillar of Microsoft’s commercial strategy in the carbon removal space is to take a portfolio approach. A mix of nature-based and engineered CDR solutions remains crucial to a successful program and provides more offtake options towards IPPC targets. Accordingly, we need due diligence and widely accepted standards to support such a portfolio approach.

Eccles: Got it. This has been such an interesting discussion. What have I missed? What are some key takeaways that you want to leave with our readers that we haven’t already covered?

Athlete compete in pole vault (Photo: iStock)

Marrs: I would reiterate that despite there being a lot of noise and real challenges in the current voluntary carbon markets, there are responsible buyers and responsible developers that are doing everything they can to help the world reach net zero. The bottom line is that we need to remain focused on deep reduction commitments and combine that with raising the bar for high quality carbon removal all while remaining transparent about our experiences and the lessons we have learned. Building new markets is hard—perhaps reforming existing markets is harder—but the stakes are just too high if we cannot keep 1.5C in reach.

Eccles: Thanks again for your time, Brian, and thanks for what you and Microsoft are doing. I’ve learned a lot, but I also know there’s a lot more to learn. But is it fair for me to say that we won’t get to a net-zero world without a robust voluntary carbon market for CDR?

Marrs: Absolutely right.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Subscribe our newsletter to receive the latest news, articles and exclusive podcasts every week