I met Joseph Noss at the launch of Liberty Mutual’s “Climate Transition Center.” At that time, he was Senior Director and Head of Financial Services in WTW’s (formerly Willis Towers Watson’s) Climate & Resilience Hub. He had previously spent over 15 years leading work on climate and sustainability both at central banks and at the Financial Stability Board. I asked Joe to speak with me about his recent paper “Emissions Impossible: Quantifying financial risks associated with the net zero transition” with the Institute of International Finance on climate transition metrics. I learned a lot.

Eccles: Hi Joe, thanks for taking the time to talk to me. Let’s start at the beginning. Please tell me a bit about your childhood.

Joseph Noss

Noss: I was born in North London. Both my parents worked in education—my mother in local government, and my father as an academic at London University. There were a lot of books in the house! But it was numbers that intrigued me, and I fell in love with maths at a pretty young age.

Eccles: What did you study at college?

Noss: I went up to Merton College Oxford in 2002 to read Mathematics. I had a fun three years. It was tough academically at times. I remember having to teach myself Galois Theory in the space of just a couple of weeks; the level of abstraction and intellectual rigour was utterly mind blowing.

Eccles: You weren’t tempted to become a pure mathematician?

Noss: No, because I was also interested in people, societies, and how they function. By the end of my degree, I wanted to apply the maths I had learned to problems involving human beings. So I stayed on at Oxford for a couple of years and took the MPhil in Economics.

Eccles: What was your first job after college?

Noss: I graduated in 2007 and was lucky to be offered a job at the Bank of England (BoE), where I wanted to pursue my dream of working on monetary policy. The BoE had recently gained independence in its setting of interest rates, and that seemed to be where all the action was.

But to my great disappointment at the time, I was put in the financial stability department. I thought this “stability” business sounded thoroughly boring. I remember complaining to the HR department: “I don’t want to work on bank failure; no British bank will ever fail!”.

A week after I started work exactly that happened, precipitated by a run on deposits at Northern Rock. Within months, we were in the grip of a full blown global financial crisis.

Eccles: It sounds like you saw quite a lot of action in the boring-sounding financial stability department after all! Tell me about your experience at the Bank of England.

Noss: I basically had a front row seat on which to view the 2008-9 financial crisis. I went on to become part of the clean-up operation, and worked on the design of macroprudential policy, negotiating parts of the Basel III accord, and running a team charged with assessing “systemic risks” to the financial system.

I also got to work with some very talented colleagues, many of whom I remain friends with to this day. They include my friend and co-author of my recent paper, Katie Rismanchi.

Eccles: We’ll come to talk about that paper in a moment. But first tell me how did you come to work on climate change and sustainability?

Noss: One day I got a call from the office of the new BoE Governor, Mark Carney. He wanted to know what we had in terms of analysis of the effects of climate change on the financial system. The answer was, basically, nothing! I had a few weeks to cobble together some ideas and analysis, with almost no data or models.

Eccles: Terrible data, no models. Wasn’t that lack of rigour abhorrent to your inner mathematician?

Group Of Friends Enjoying Drink In Bar (Photo: iStock)

Noss: Far from it. It was part of what attracted me to climate and sustainability issues.

And speaking of attraction, the work had other benefits. One night I got talking to a girl in a bar. She asked me what I did for a living. Now that’s always a terrible question to ask a mathematician-turned-central-banker. There’s just no way to make your work on systemic risk sound…well, sexy. So, I told her I worked on climate change—much more cool-sounding!

I got her number, and we’re now married with a young daughter.

Eccles: Excellent. And a great tip to all the maths geeks out there. Get into climate. It helps you meet your partner. I studied maths at MIT but lack your social skills. I met my wife on a blind date and told her about my book on transfer pricing.

Noss: Wow, and she married you?

Eccles: Fortunately, she did! And happy to tell you the story over a pint someday. But back to you. Tell me a bit about your time working for the Financial Stability Board.

Noss: By 2018 I was getting itchy feet. I moved to Switzerland to join the Secretariat of the Financial Stability Board where I led work on climate change. It was an interesting time. Some financial authorities—including central banks—were becoming increasingly concerned about the risks climate change posed to the financial system. OtherS— including those in the US, which at this point was in the grip of the Trump presidency—were less convinced. Squaring off those views and driving agreement on G20 papers and policies was absolutely fascinating.

Eccles: And now you’re back in the UK?

Noss: That’s right. Late in 2021 we returned to London. I was keen to try working for the private sector, and to see how financial institutions really worked up close. I went to work for WTW. One of the fascinating things about the firm was the investment they’d made in the rigorous measurement of climate risks. The techniques and technology were just fascinating. I got to lead and work with teams of climate scientists, academics, engineers, and geographers. My inner maths geek was in his element!

Statistics chart on increase in CO2 emissions and their decrease compared to previous years. Reduce CO2 emissions to limit global warming. Ecological and clean future.(Photo: iStock)

Eccles: And it was there while working at WTW earlier this year that you and some colleagues published a paper on transition metrics. Please tell me a bit about that.

Noss: Our paper was motivated by the observation that financial institutions were—and continue to be—expected to quantify their exposure to climate risks, and the degree to which they are sustainable more broadly. But there wasn’t at the time (and I’m not sure there is now!) an agreed set of high-quality decision useful metrics through which they can do so.

Eccles: What’s the key contribution of the paper?

Noss: It’s vitally important that we, both the preparers of sustainability/climate disclosures and those that use them, understand the information that’s being conveyed in the disclosures. In the paper we step through the sort of information that are commonly included in metrics related to firms’ transition to net zero and their transition plans. These are broadly divided into three types:

- Transition risk: that is, the financial risk that transition to a lower-carbon economy poses to a company. You can think of that as the potential negative impact on the profitability of a business from changes in policy, regulation, technology, and consumer preferences.

- Climate impact: that is, the impact of a firm on the climate via its emissions.

- Transition impact: that is, the degree to which a firm’s activities facilitate transition to lower emissions in the real economy. One example might be a firm engaged in the mining of minerals such as lithium, which is used in the manufacture of electric vehicle batteries.

Eccles: In the paper you talk about the degree to which those types of information are sometimes conflated. Is that right?

Noss: Absolutely. Information on climate and transition impact is sometimes found in metrics that purport to capture information on climate transition risk. For example, there are several instances of emissions-based metrics being proposed or indicated as proxy indicators of climate transition risk.

On the face of it, this seems intuitive. After all, any increase in the cost of emissions—for example, that which is brought about by the introduction of a carbon tax—is likely to result in carbon-intensive firms facing higher costs that can reduce their profitability, and increase, say, their risk of default.

However, emissions-based metrics do not provide a comprehensive indication of a company’s overall exposure to transition risk.

Young Confident Businessman Jumping in Blue Sky Between Boulders (Photo: iStock)

Eccles: Why not?

Noss: For three reasons.

First, the reporting of emissions is subject to systematic biases and gaps. For example, a software company serving firms in the oil and gas industry might report only very limited emissions, but to the extent that demand for its services is likely to reduce under climate transition, it might be exposed to substantial climate transition risk. Even Scope 3 emissions, which seek to reflect emissions arising from the entirety of firms’ value chains, struggle to capture emissions arising from the activities of firms that use a product or service and are subject to various data gaps. This limits the availability of information on firms’ emissions, and the subsequent effects of a carbon tax on their profitability, across different sectors.

Eccles: Measuring Scope 3 is hard and especially controversial here in the U.S. It will be interesting to see how the SEC’s final climate disclosure rule deals with it. But what’s the second reason?

Noss: Current and historical emissions, whatever their scope, are backward-looking and give only very limited insight into future changes in firms’ business models. Future changes in firms’ emissions can be a crucial determinant of the transition risk to which they are exposed. For example, a manufacturing firm that is currently heavily reliant on energy from fossil fuels might be planning to switch to using renewable energy.

Eccles: Got it. But at least this gets companies thinking more about their carbon emissions, doesn’t it?

Noss: It does. But this gets me to the third reason. Even if the above measurement issues were resolved, an increase in the cost of emissions may not necessarily be associated with an increase in the transition risk to which a company is exposed. This is partly because some firms might experience a large increase in the cost of emissions, say, as a result of the imposition of a carbon tax, but nonetheless still see continued (or increasing) demand for their products (price inelasticity of demand), or otherwise be able to “pass through” increased costs without their profitability being affected.

So, a firm’s emissions and the risk they present to, say, the bank that finances them, are quite different; more-or-less orthogonal, to use the mathematical term!

Eccles: Interesting. Is that orthogonality between emissions and risk born out empirically?

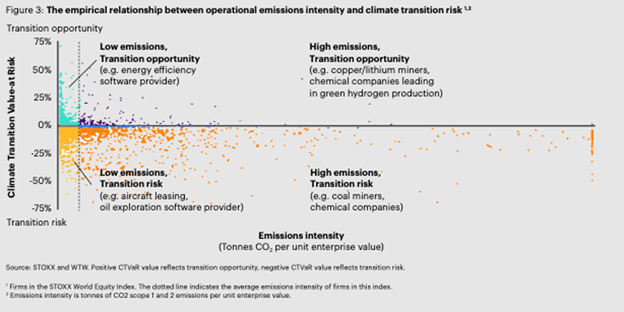

Noss: Yes, absolutely! In the paper we compare the emissions intensity and climate transition risk of over a thousand firms in the STOXX World Equity Index. You can see the results in the figure below. There is little, if any, correlation between the two. Some firms, for example those involved in mining lithium or cobalt for use in batteries, might give rise to high emissions. But because the materials they extract are enabling reductions in emissions elsewhere they might be quite profitable in future. Other firms are lower emitting. But suppose that’s because they’re a software supplier to the oil and gas industry. A firm like that is going to also be exposed to substantial transition risk.

The Empirical Relationship Between Operational Emissions Intensity and Climate Transition Risk

Eccles: What does that insight mean for policy, do you think?

Noss: To me it underlines the importance of understanding and clarifying what information a metric is intended to capture and using it appropriately. If emissions were taken as a direct measure of transition risk that could have quite damaging consequences, both for individual firms’ risk management, and for broader net-zero transition. For example, if a bank sought to reduce its exposure to high emitting industries, it might inadvertently cease to fund even those likely to remain profitable through the transition. In addition, it might also slow transition in the real economy if that high emitting firm is reducing emissions elsewhere in its supply chain.

Eccles: This is a very important point which I think is ignored too often by the advocates of “no more money to the high emitters.” Next question. What do you think the right metric is then, at least when it comes to thinking about transition risk? Where should regulators settle?

Noss: I think the key thing to understand is that there’s no single “right” metric. Different metrics have different pros and cons.

Some providers, including WTW where I used to work, have developed Climate Transition Risk metrics that provide a reasonably risk-sensitive view of how the net-zero transition will affect firms. These metrics generally consider a broader range of factors, such as changes in consumer sentiment, technology, and regulation that are likely to affect firms’ profitability during transition. As such, they may be suitable for financial firms’ internal risk management.

But these sorts of metric tend to be based on a large number of data sources, and their calculation requires considerable human judgement: For example, to decide how a given transition scenario will impact different economic sectors. This makes them harder for third parties to verify and might make them less suited to use in public disclosures.

On the other hand, some metrics are far simpler and easier to verify, but don’t directly measure transition risk. For example, some standard setters—including the TCFD, the ISSB, and the European Union (under the guise of its Green Asset Ratio)—have proposed that the proportion of a financial institution’s exposure to “carbon-related assets” or carbon-intensive sectors as a summary metric for financial firms’ transition risk. This is nice and straightforward and requires far fewer complex calculations but is far from a comprehensive measure of risk.

Eccles: So, you have measures that are very sensitive to risk, albeit at the cost of complexity. or measure that are simpler, but that provide a much less faithful view of risk?

Noss: Absolutely. And that trade-off should be quite familiar to financial regulators. If you look at the way we measure other sorts of risks in, say, banks, we have risk-sensitive capital requirements that levy different levels of capital on banks depending on the riskiness of their assets. At the same time, we have blunter tools, such as a minimum leverage ratio, which is more straightforward to calculate, but that doesn’t account for differences between the risks to which banks are exposed. The key is to understand the information contained in each sort of measure and put it to appropriate use. Climate transition risk is no different.

Eccles: Thanks for your time and I’ve learned a lot. let’s keep in touch!

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Subscribe our newsletter to receive the latest news, articles and exclusive podcasts every week