Earlier this year I had the pleasure of being a guest in an executive education course at Columbia Business School being taught by my good friend Professor Shivaram Rajgopal. I was on a panel with James Andrus of Franklin Templeton and Thomas Kamei (TK) of Morgan Stanley Investment Management. One of the topics we discussed was the integration of sustainability into investment decisions and funds focused on doing so. I was very interested in what TK had to say so arranged to have lunch with him when I was next in New York. I’m doing an interview with him and asked if he had suggestions of other investors doing similarly interesting work. One of the names he gave me was Lee Qian of Baillie Gifford where he manages their Positive Change Strategy. TK kindly put me in touch with him. I was impressed with what Lee was doing as well and asked him if he’d also be willing to do an interview. He kindly agreed.

Lee Qian, Investment Manager, Positive Change Strategy

Eccles: Lee, thanks for taking the time to talk to me. Let’s start by talking about your background. I know you were born in China. What was it like growing up there?

Qian: Yes, of course. I was born in the city of Nanjing, China, in the early 1990s and spent the first 10 years of my life there. Nanjing had been China’s capital multiple times throughout history, so it was a vibrant city. The early ‘90s was also a period of dynamism and optimism. The government abandoned the Mao-era central planning and allowed private enterprises to play an increasing role in the economy. People started their own businesses. In fact, some of the most famous Chinese companies today, such as Alibaba and Tencent, got going in the 1990s. In general, those private companies had a tremendous positive impact on people’s lives. They were more innovative and competitive; they listened to their customers; and they provided an increasing range of products and services at lower prices than before. As businesses and the economy flourished, people’s living standards also improved. In 1990, more than 70% of the Chinese population lived in poverty, but 10 years later, that fell to below 50%. It was incredible.

Eccles: Sounds like that was very exciting environment to be growing up in!

Qian: It was! Growing up in China in the 1990s deeply influenced how I see the role of businesses in society. I fundamentally believe that a free and competitive market is an engine of prosperity and progress. It’s a much more efficient way of allocating resources; it incentivises innovation; and it supports higher incomes and living standards. Today, capitalism receives a lot of criticism, and of course, the system is not perfect and can be improved upon. Nevertheless, if we are to solve challenges like climate change, epidemics, and job displacements we will need to tap into our entrepreneurial spirit.

Eccles: That’s fascinating, and I completely agree. I am sure we will come to the latter point later on. But you mentioned that you lived in China for 10 years. What happened afterwards? Where did you go?

Qian: When I was 10 years old my parents found jobs in the UK, and I moved there with them. We eventually settled in a small town called High Wycombe, just outside of London, and I went to school there.

Eccles: And did you go to university in the UK, too?

Qian: Yes, I did. I studied Economics and Management at Oxford.

Eccles: Great, and how did you get into investing?

Qian: At university, I became very interested in the management part of my degree, including topics like strategy, competitive advantage, organisational behaviour, and marketing. Towards the end of my degree, I was focused on finding a business-related job, either with a consulting firm or in the industry. However, a friend told me about this Scottish investment company called Baillie Gifford with a great reputation and culture. I did some research and found its investment management trainee programme. At that time, I did a bit of investing on the side, but I never seriously contemplated a job in the investment industry. Nevertheless, the more I read about it, the more interesting it became, so I decided to apply.

Eccles: How did it go?

Qian: When I went up for the interview, what became immediately clear was that the company had a truly long-term horizon, which influenced both its approach to investment and training. Furthermore, the job itself was really interesting. The role of a fundamental equity investor is to analyse businesses, their growth prospects, competitive advantages, and financial characteristics in order to determine if they had the potential to become good investments. I thought, at a minimum, this was a great way to learn about what makes businesses successful. Fortunately, I passed the interviews and received a job offer.

Baillie Gifford Logo

Eccles: Congratulations! Can you tell me a little bit about Baillie Gifford?

Qian: Yes, Baillie Gifford is an investment management company. Investment management is our only business, and our clients include pension funds, endowments, financial institutions, intermediaries like wealth managers or advisers, and individuals. The company has been in existence for more than a century, and today, is still privately owned by 58 partners who all work at the company. It has $284 billion of assets under management as of June 2024. We don’t have outside shareholders, so we are not burdened by quarterly earnings or short-term pressures. This enables us to adopt a long-term investment philosophy. Most of our equity investment teams are growth-focused, meaning we are looking for companies that can deliver superior revenue and sales growth over the long term – five to ten years or longer.

Eccles: Great. And now you’re involved with a strategy called Positive Change. What is Positive Change and how did it come about?

Qian: Towards the end of my investment trainee programme at Baillie Gifford I started thinking about what I wanted to do with my career. And I returned to this idea that businesses, when done well, should have a positive impact on society. At the same time, sustainability challenges were rising up the agenda, so I wanted to learn more about this. I took a Coursera course on sustainable development, and I realised the importance of having a long-term horizon. Solving challenges like reducing poverty or addressing climate change will require years and decades of investments. If companies are only focused on their quarterly or annual profits, they would be unlikely to make the necessary investment in innovation that’s needed to address sustainability challenges. I thought this aligned well with Baillie Gifford’s long-term culture.

Eccles: Makes sense to me so what did you do next?

Qian: After more research, I wrote a proposal for a new investment strategy called Positive Change. At the time, many responsible investment strategies were focused on using exclusionary criteria, such as screening out oil and gas companies or tobacco companies. There were many issues with that, and I thought there must be a better way. The thesis for the Positive Change strategy was that rather than focusing on avoiding harm, let’s focus on the solutions. Let’s create an investment strategy where all the companies are making a positive contribution towards a sustainable future.

Man pulling the curtain up to a new colorful world. Power to make a change for the better. (Photo: iStock)

Eccles: That is music to my ears. Can you please explain to me what the Positive Change strategy looks like in practice? Are there particular areas you focus on?

Qian: Of course. The first thing to say is that we are looking for companies whose products and services help address sustainability challenges. This isn’t simply about having nice business practices, such as an ethical supply chain or installing solar panels on the factory roofs. Rather, we are looking for companies whose products and services are contributing to a more sustainable and inclusive world. Those could include novel medicines, electric vehicles, equipment for modern water infrastructure, or financial services for the underbanked or unbanked. By focusing on product impact, we believe it creates a nice alignment between sustainability outcomes and the interests of the shareholders. Selling more products increases the companies’ sales and profits and their overall impact.

In terms of our investment remit, Positive Change is a global strategy so we can invest in companies regardless of their location. Today, roughly half of the companies are based in the U.S., with the rest spread out across Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. We have four impact themes, which are Social Inclusion & Education, Environment & Resource Needs, Health & Quality of Life, and Base of the Pyramid. The last one is focused on businesses that are addressing the needs of people who live on low incomes across the world.

Eccles: Positive Change is a public equity portfolio. Can you talk about what type of impact you can have as an investor?

Qian: Good question, we get it a lot, and happy to. With the exception of when a company does an IPO or a secondary offering, we purchase shares on the stock markets from existing shareholders who are selling their shares. Some people have argued that public equity investors can’t have an impact because they are not providing primary capital. This is a very important point. It emphasises the fact that in public equity, simply owning “sustainable companies” doesn’t make the investment strategies sustainable, in the sense that they are contributing to real-world sustainable outcomes. However, public equity investors can still make important contributions through their investment activities.

Eccles: How so?

At Positive Change, we believe the impacts we can have as investors come from our time horizon and engagement activities. Our portfolio turnover is low, typically around 10-20% per annum, which equates to an average holding period of 5-10 years. As mentioned earlier, a long-term horizon is absolutely crucial for sustainability. When we meet with management teams, we emphasise to them that we are investing in their businesses with a long-term mindset and we encourage them to make long-term investments, be that in product innovation or their workforce. We believe that management teams will find it easier to make those types of investments if they know long-term shareholders are on their register.

On engagement, we believe it is most effective when we have the trust of the management teams, and we discuss sensitive topics in confidence behind closed doors. We suspect that sometimes the high-profile shareholder proxy fights serve more to raise the profiles of the investors than actually improve the companies. Therefore, we invest a significant amount of time upfront in building relationships with the management teams before contentious issues arise. When those issues do arise, we are in a much better position to influence management and the board. For instance, we have had very productive discussions with Stephane Bancel, CEO of Moderna, on vaccine pricing and access. With one of our investee companies in the water sector, we have had useful engagements with the board on governance and remuneration.

Eccles: Thanks for the explanation. Sounds like you have very constructive relationships with your portfolio companies.

Lee: We do.

Man hiker flexing his muscles in hiking celebration. (Photo: iStock)

Eccles: Next question. How do you measure and report on impact?

Qian: Impact reporting is not straightforward. Because the Positive Change strategy invests in a wide range of companies – including those offering breakthrough medical treatments, electric vehicles, and financial services in developing countries – there is no single metric that can describe the impact of all the portfolio companies. Furthermore, certain impacts can’t be quantified. Think about the social benefit of improving access to education or information technology. Nevertheless, we believe it’s absolutely crucial to report on impact to demonstrate the credibility of the strategy. To that end, we produce two annual reports, one focusing on the product impact of the portfolio companies, and the other one focusing on business practices and our engagement efforts. [You can access the latest version of the Annual Impact Report here and the Positive Conversation Report, detailing business practices and engagement efforts, here]

For product impact, we use a framework based on a Theory of Change that examines how a company’s products are connected to an end impact, such as improving health outcomes or reducing poverty. We do this for all the companies in the portfolio to ensure transparency. We don’t just cherry-pick a few nice examples. Where there are negative impacts, we also report on those. At a portfolio level, we use the UN Sustainable Development Goals, a widely recognised framework, to communicate the impact of the companies. In instances where several companies report their product impact in the same way, we can also aggregate their impact.

For business practices, we detail companies’ approaches to environmental, social, and governance factors and their policies on managing any negative impacts in those areas, such as greenhouse gas emissions. For engagement, we report our interactions with the management teams throughout the year, and the goals and outcomes of those meetings. We also disclose our proxy voting decisions.

Eccles: Thanks for the explanation. Can you give me a few concrete examples?

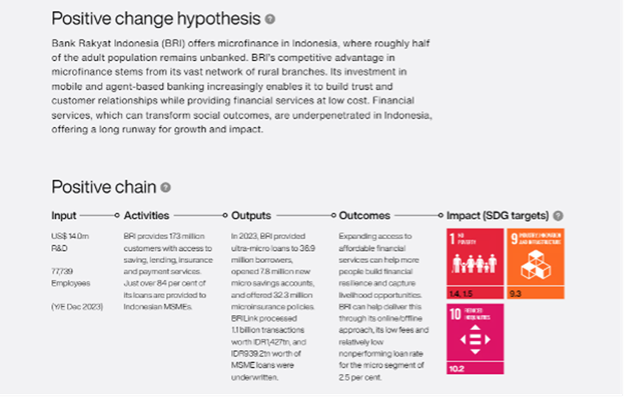

Positive Change Hypothesis Chart for Bank Rakyat Indonesia

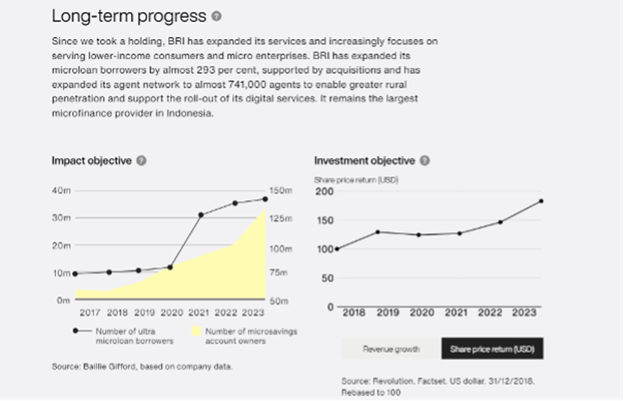

Yes, I can. For product impact, consider Bank Rakyat, a microfinance institution that serves millions of customers in Indonesia. In our Impact Report, we highlight our investment hypothesis and describes how the company’s activities and outputs lead to positive societal impact. We map those impacts onto the UN Sustainable Development Goals. We also show how the product impact have evolved over time. In the case of Bank Rakyat, we tracked the number of micro-loan borrowers and micro-savings account owners. We compare that against the share price return and find a positive correlation between product impact and investment outcome.

Long-Term Progress at Bank Rakyat Indonesia

Eccles: Let’s move to Positive Change’s financial objective. There’s always a question about whether it costs money to do good. What do you think about this?

Qian: Yes, there have been a lot of academic studies on this question. With so much empirical data out there, one could probably always find something to back up their view. Ultimately, the most important factor determining the investment returns is the quality of the fundamental business analysis, rather than sustainability. You can make or lose money by investing in sustainable companies, just like you can make or lose money from investing in unethical companies. What matters to whether you make money or not is if you are a skilled stock-picker.

Eccles: That’s very clear. I just wish more people interested in sustainable investing had that kind of disciplined clarity.

Qian: For us there is no other way. At Positive Change, while we focus on businesses that are contributing to a sustainable world, we ensure that this doesn’t detract from our fundamental company analysis. For all the investment candidates, we conduct investment research that examines the growth opportunities, competitive advantage, management team, financial characteristics, and valuation, just like all other equity teams at Baillie Gifford. We would only invest in companies that we believe have the potential to outperform the global equity benchmark over the next five years.

If that’s the case, one could ask why we should focus on sustainable companies at all, if it doesn’t have a significant impact on investment returns. The answer is that the public equity investment universe is incredibly large, and investors always need a way to filter that universe and decide what type of companies to focus on, be that valuation, market cap, or geography. We believe defining our investment universe based on sustainability can be a useful way too, as we spot some similar characteristics across those companies that over time help us hone our craft as stock-pickers.

Eccles: I like the way you frame this. You also make a good point about finding common characteristics. Last question and I’ll let you get back to your Day Job! What’s the long-term ambition for Positive Change? What does success look like?

Qian: We want to show that investors could do good and do well at the same time. We want to generate attractive long-term investment returns for our clients and support companies that are making a positive contribution to society. We want the impact of our investment activities to deepen. Most likely, that would point towards investments in private companies over time, where we can provide primary capital to companies to help them fund research and innovation.

Eccles: Thanks again for your time, Lee, and I wish you your Positive Change team the best of luck!

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Subscribe our newsletter to receive the latest news, articles and exclusive podcasts every week